Getting ready for exhibition in August

For nearly two years I have been accumulating pictures in my workroom. Three weeks ago I cleared it out, and selected my favourites to be photographed. Now I am starting to frame them - a fairly chaotic process for the rest of the house, as they spill out into the kitchen and lounge room.The exhibiton, called '600 days - Landscape & Still-life', opens on Aug 17 at King Street Gallery on William and runs until Sept 10. For the first time I will show still lifes of food as well as a few pairs of shoes.

'The art that made me' Look Magazine

Tom has written about four works in the Art Gallery of NSW collection for Look Magazine (Art Gallery Society of NSW) September issue 2015

Archibald and Sulman Prizes 2015

Tom's paintings were selected for the 2015 Archibald and Sulman Prizes at the Art Gallery of NSW.

Sulman: 'Sydney Structures' watercolour and pigment ink on paper 15 sheets 16 X 11 cms 2015

Sulman: 'Sydney Structures' watercolour and pigment ink on paper 15 sheets 16 X 11 cms 2015

Archibald: Self Portrait at 60 oil on linen 22 X 18 cms 2015

Archibald: Self Portrait at 60 oil on linen 22 X 18 cms 2015

Seven Walks

Robert Gray - selected poems

A new compact edition of Robert Gray's selected poems has been published by Black Inc Books, using a painting of Scotts Head by Tom Carment on the cover. This book has been printed in a large numbers, as it has been selected for Higher School Certificate English.

Tom Carment wins NSW Parliament Plein Air Painting Prize 2014

Postcards - an essay by Tom Carment in Artists Profile issue 27 May 2014

Postcards

There is a stained white shoebox on our bookshelf in which I keep my collection of several hundred art postcards. I have been collecting postcards of paintings and drawings since the mid 1970s, mostly from art museums and some from second hand bookshops and market stalls. I buy duplicates of the ones I really like – one to keep and one to write on and send. Every now and again I pull the box down, open it up and shuffle through them, picking out a few that appeal to me. The new selection gets pinned to the wall of my studio or put under a magnet on the fridge.

Sending and receiving postcards is great pleasure to me. To write a good postcard is not always easy: you have limited words with which to communicate news, crack a joke, make an observation and send love. In fact it is not dissimilar to the modern day limitations of tweeting. If I have too much to say, I use both sides of the vertical divider, which means the card has to be placed in an envelope. My writing often starts out expansive and decreases to tiny as the space diminishes, with afterthoughts sliding up the sides like marching ants.

For Australian artists of the pre-digital age, art postcards were objects of yearning -- images of a culture lodged far away, in museums across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. For those who had made the pilgrimage to these places, they became souvenirs.

If you look at photos of artists’ studios there are usually a few postcards in there somewhere, thumbtacked or taped to a wall, beside a doorjamb or next to a light switch.

The size of a postcard is set by the maximum dimensions for the standard postal charge. They fit in the pocket or can be used as a bookmark. ‘Postcard-sized’ has become an informal unit of measure. The image on the card can change over time, from exposure to light, and accrete a patina of dirt and damage. After a while, whether I have actually seen the original painting reproduced on the card becomes less important.

The other week I went through the postcard box again and chose six cards to write about in this essay. On another week I might have made a completely different selection.

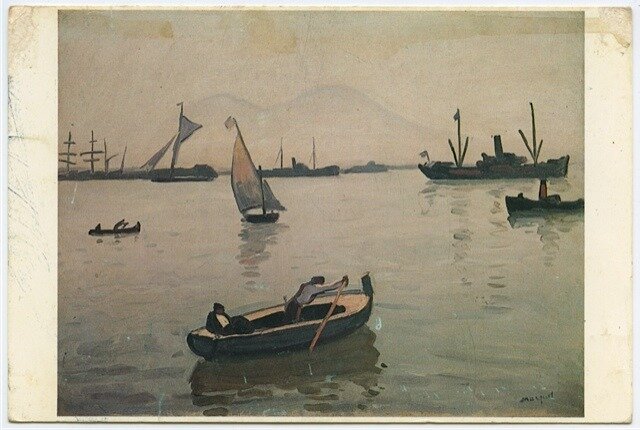

Albert Marquet (1875-1947)

Naples 1909 oil on canvas

Johannesburg Art Gallery

Albert Marquet is generally placed with the Fauves of the early 20th Century -- Derain, Dufy and others. However, by 1909, he was moving away from brightly-hued Fauvist interpretations of landscape, to a more naturalistic use of colour, in this case, the luminous haze of the Bay of Naples. Marquet often painted ports, Tangier, Le Havre, Amsterdam; but I think the series he did on two trips to Naples before 1910 are the acme of his depictions of water and the life on it. They have an exuberant energy about them. Marquet often put transient things into his pictures: pedestrians in a hurry, boats on the move. His paintings are about what happened on a particular day.

Arriving in a new port, Marquet and his wife would take pains to find a hotel room with a busy scene to be had from its window or balcony. Given its low perspective however, I think this picture was done at an easel, close to the shore. Marquet painted quickly, always from life, ‘alla prima’, with a thin creamy impasto.

In 1986, I actually visited and swam out across the Bay of Naples, from close to where Marquet would have painted. It was a summer day and the outline of Vesuvius looked much as it does in the painting. People were sunbaking, eating precariously-balanced picnics on the jagged rocks of the shore, listening to radios, but no-one was swimming. My girlfriend and I jumped in and crawled out through the none-too-clean harbour for a few hundred metres, then trod water in the middle of the bay. A rowboat, piloted by shirtless teenage boys paddled nearby. They called out to us and we looked up. One of the boys was standing up in the boat, making it tip towards us, holding, cupped in his hand, his erection. They rowed off laughing.

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) Portrait of Don Ramon Satue 1823

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The portrait by Goya was stuck for years above my carpentry workbench. This bench is where I sand off paintings that I don’t like any more, so the man’s contemptuous look was appropriate. Goya’s sitter is so insouciant and self-assured, at home in his own soft skin. It has recently been discovered that this image of Don Ramon Satue, a judge, was painted on top of another portrait -- a medalled military man, perhaps French, Napoleonic. It was probably politic of Goya to cover it with the portrait of a Spaniard.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

Limestone Cliffs on the Island of Rugen 1818

90 X 71 cm Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur, Switzerland

When the German writer Heinrich von Kleist first saw Friedrich’s painting Monk by the Sea, he said that it felt like his eyelids had been cut off. It was a similar revelation for me when I first some Friedrich paintings in real life, in the 70s. Previously I had thought them a bit kitsch.

This painting of a ravine between cliffs by the sea is like a scene from an 18th century novel. It was painted just after Friedrich’s honeymoon to that region. I jokingly call it ‘where’s the ball gone’ but in fact I‘m sure the woman in the red dress has lost her bonnet, blown down between the cliffs and the man crouched on the grass, dressed in blue, is contemplating its retrieval. The third figure, a male in a floppy hat, seems disconnected from the small drama to his left and stares out to sea watching the two white sails. The composition is a sort of tunnel, the ocean, gestalt-like, could be a mountain if the picture were to be inverted.

The figures in Friedrich’s art nearly always stare away from the viewer into the world of the painting which seems to have its own inner glow.

After losing his mother early, Friedrich, aged thirteen, saw his younger brother drown, falling through the ice on a lake. He had a reputation, later in life, for being a melancholic loner. Yet there is a contemporary account from his years in Dresden, round 1808, that says he was good company, humorous and kind. It relates how the artist used to let the local children come into his studio to watch him paint. One little girl kept asking him to give her a picture, and so he gave her some of his pencil drawings. One day he asked her what she did with them and she replied that she used them ‘to wrap her things in’.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) La Folle 72 X 58 cms Musée des Beaux Arts, Lyon

After his mental breakdown in 1819, Géricault painted ten studies of people with different types of madness. He apparently gifted them to a Doctor Georget, who had cared for him. It was a time when the French were at the forefront of an effort to improve the treatment of the mentally ill. Five of the portraits in this series have been lost, but five were discovered in an attic in Baden Baden, forty years after they were painted. They were amongst the artist’s last oil paintings. This portrait (sometimes entitled, Monomania of Envy and The Hyena) is so direct; free from any anxiety about style or the desire to please either the viewer or the sitter. Those fierce red-rimmed eyes, peering sideways, are difficult to forget.

Géricault, famous for his dramatic canvas, ‘Raft of the Medusa’, died young as the result of three riding accidents. He was fascinated by the macabre. Near the end of his final illness he had the surgeons set up a mirror so that he could observe them excising a malignant tumour from the base of his spine. He claimed that viewing his own anatomy helped him cope with the pain.

Ghirlandaio (1449-1494) Portrait d’un viellard et de son petit-fils

Musee de Louvre, Paris

I know little about Ghirlandaio, but I think this painting of an old man and his grandson is one of the great double portraits. The child, his vision unpolluted, sees only a familiar kindness in the face of his grandfather. The man’s nose is deformed with a growth, Rhynophyma, and there are thick black hairs sprouting from his forehead and down the bridge of his nose. It looks almost as if someone has hacked lines into the paint with a knife, such is their jagged proliferation. There is a melancholy smile of appreciation on the face of the old man, as though he fears that soon, under the influence of peers, his grandson will revile him; or that soon he himself will die and never see this boy grow into a man.

References:

Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer Theodore Gericault Phaidon 2010

Marcelle Marquet Marquet – Travels International Art Books Lausanne 1969

Gail Levin The Complete Watercolours of Edward Hopper Whitney Museum of American Art New York 2001

William Vaughan, Helmut Borsch-Supan, Hans Joachim Neidhardt

Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840 Romantic Landscape Painting in Dresden

The Tate Gallery 1972

Tom Carment 2014 www.tomcarment.com

James Waites

Jim (James) Waites died 12/2/14. He went for a last swim in the sea at Coogee early on a Wednesday morning

Jim was mainly known as a theatre critic, writer and commentator. Recently, he kept a theatre blog, and made long interviews with theatre people for the National Library of Australia.

We first met in 1976 and he has, since then, been a most consistent friend. There were gaps when we didn't meet for years but then, when we caught up, it was just like we'd seen each other yesterday. Despite the fact that I wasn't much of a theatre-goer, there was always so much to talk about. He supported my painting and writing from early on, and introduced me to people who became patrons and friends. Jim was very inclusive, and had a wide-ranging group of acquaintances. His enthusiasm was a real boost to me and I imagine there are many others who would vouch in a similar way for his kindness and support.

I painted about six portraits of Jim over the years. The one shown above was done when he lived in a big dark-brick bungalow in Rosebery, in '98 or '99 I think. His face and appearance were quite changeable from month to month, especially when his hair grew and went curly. After he was bashed up on a train a few years back, I did several portraits of his battered face as as he lay on his bed recuperating. As a portrait subject he had no vanity.

One Christmas we all went on holidays to to the Caravan Park in Yamba, and Jim organised a treasure hunt, for the children. I rowed them over to an island in my small boat, across the estuary, where Jim had left clues that led to hidden objects.

Jim will be missed by his many friends.

Utzson's Opera House

Tom Carment had watercolours in the 'Utzon's Opera House' exhibition at the S.H.Ervin Gallery Observatory Hill, from Dec 2013 until Jan 2014

On Sunday Dec 15 2013 he gave a talk there with Peter Kingston and Wendy Whiteley.

Here is the text of his talk:

Tom Carment talk – Utzon’s Opera House

15/12/13

It’s hard to think of a building so modern and so audacious being 40 years old -- indeed its design was conceived over 50 years ago. My pulse always quickens when I approach the Opera house. No matter which route I take to approach it, through the Botanic gardens with its bats, palm groves and joggers, or around from Circular Quay; its onset is dramatic. It’s such an exuberant building.

And, apart from its exterior form, it is also a huge repository of memories -- memories of times when we forgot about our everyday lives, about our humdrum affairs and were swept away to somewhere else.

These days Opera House performances embrace a wide audience -- not just the traditional concert-goers in their powder and pearls but proud parents relaxed in shorts and thongs who’ve come to hear their kids sing and play recorder in a public schools concert of a thousand, or crowds of young people on the steps watching the final of Australian Idol.

In the late 60s and into the 70s I must have travelled past the Opera House construction site many times on the ferry, or crossing the bridge, but I regret to say I missed most of it - lost in the fog of my adolescent self-regard. Too busy worrying about my pimples. I have a vague memory of dogmen on girders. and white bones of concrete sticking up from Bennelong Point.

About eight years ago I had the privilege of being artist-in-residence on a city building site in central Melbourne and was fascinated by the drama of the whole construction process. The Opera House site would have been a wonderful place to draw and paint, its action directed by hand signals, whistles and shouts. It was in the days before computers when architects wore bow ties so as not to smear their drawings. There would have been an army of people hand-drafting and altering the complex plans.

During the eighties I worked for a lady who created painted finishes, very popular in that era. We spent a week making a rock-like effect in red and yellow ochres on the high walls of the Opera House aboriginal art shop -- not there any more. I would walk through a labyrinth of concrete corridors down into the bowels of the building to wash our brushes.

I guess we all have memories too of the performances we’ve seen on Bennelong Point. In my case its not much opera, but mainly concerts and plays. One of the first was Jim Sharman’s production of Patrick White’s ‘Season of Sarsaparilla’ in 1976 and much later his version the play ‘Three Furies’ about the painter Francis Bacon. Recently, I’ve watched the energetic Vladimir Ashkenazy in his white skivvy conducting Prokofief, seen Clive James in an armchair in front of the Symphony Orchestra as he explained a program of obscure film music. In the last decade my children have been performing there – my son sings in a men’s choir called Vox who provide choral support to the Sydney Symphony. I saw him singing in Norwegian, during Grieg’s Peer Gynt.

About 15 years ago a friend who worked in props would sometimes give me free tickets to daytime dress rehearsals of operas. One time it was Don Giovanni, and it was a day that I was looking after my four year old son. He was a quiet kid and liked music, so I decided to take him along, see how it went. We didn’t last long ... in the first act Don Giovanni forced himself against Donna Anna the Comandatore’s daughter, pushing her roughly up against the side of the stage trying to lift her skirts. My son called out loudly : ‘No, No!’ The usher rushed over and showed us the exit and berated me for bringing such a small child to the opera.

I appreciate the strict codes of behaviour they have at the Opera House, like stopping people taking photos and using their phones during performances, from talking, and coughing too much, but I’m sure Mozart would have approved of my son’s outburst. In his day I feel sure, operas would have been punctuated by the audiences’ passionate reactions. I think concert-goers these days are perhaps too polite – they clap away at a recital that has not particularly moved them, and almost never express discontent. Maybe they are just happy to be inside the Opera House, and would listen to someone gargling for an hour just for the excitement of being there.

About five months ago Peter Kingston sent me a postcard asking if I had ever, or would like to, depict the Opera House for this exhibition. I replied the next day with another card saying that I wasn’t sure about painting the sails as they were art in themselves, but would have a go at painting the steps. I wrote that that I liked the way people always gathered there.

And so, thanks to Peter’s suggestion, I commenced my series of small watercolour and ink pictures.

I’ve always loved the Opera House steps, the way they go up and up, at a gentle enough incline to make ascending them easy and relaxed. I think they must be the largest and widest set of steps in the country. It is said Utzon was inspired in their design by Mayan temples. They are like the wake that follows the roofs.

I also find it interesting that people love being and meeting on steps in general, perhaps more so than they do in a flat square or piazza. The Utzon steps provide groups of people so many varieties of position in which they can congregate, whether sitting in a row or standing, and they afford dramatically foreshortened views of the shell roofs as well as long views, way up the harbour, to Manly.

And so, in October, I commenced my small project. I’m lucky to live a forty minute walk away and so I would put my watercolours in a backpack and either walk through the Botanic Gardens or ride my bike to Bennelong Point. Then, after deciding where I was going to sit on the steps, I would get out my two watercolour plates, my folder of cut up pieces of Arches hot-pressed paper, a roll of tape so the paper wouldn’t blow away, and my tube of different-sized sable brushes. I commenced each picture with a line drawing done with a pigment ink pen. I use a variety of pen whose ink dries quickly and does not bleed when, in the second phase of my process, I apply washes of watercolour over it. Sometimes at the end I add a few more black lines with the pen.

There is an open gap under each of the long Opera House steps, and, being aware that my brushes might roll or get blown down into it, I took care to place them beside a rubber grommet that is wedged in the gap every few metres. One windy day however a gust blew two of my best sables forward and down into the void. There must be a lot of stuff lost in that irretrievable space.

Groups of visitors came and went as I painted and drew -- Chinese tourists fresh off their coaches, office workers taking lunch breaks, wedding photographers with bride and groom, audiences early for the matinee of ‘South Pacific’. Many of them were holding their mobile phones, ipads and digital cameras out in front of them, taking thousands of snaps of the sails. Often the partner was made to jump in the air in front of them, doing the v sign at the same time. The modern camera or device, I noted, is no longer held close to the face.

Because I was working small, and perhaps because I look like a crazy old coot, people left me alone. Even the security guards; who may have noticed that I was reappearing there each day and was sitting in one place for some time. The seagulls would assume that I was opening a sandwich and crowd eagerly around, but soon got bored and flew off. ‘Don’t you just hate watercolourists’, they’d be saying to each other.