Postcards

There is a stained white shoebox on our bookshelf in which I keep my collection of several hundred art postcards. I have been collecting postcards of paintings and drawings since the mid 1970s, mostly from art museums and some from second hand bookshops and market stalls. I buy duplicates of the ones I really like – one to keep and one to write on and send. Every now and again I pull the box down, open it up and shuffle through them, picking out a few that appeal to me. The new selection gets pinned to the wall of my studio or put under a magnet on the fridge.

Sending and receiving postcards is great pleasure to me. To write a good postcard is not always easy: you have limited words with which to communicate news, crack a joke, make an observation and send love. In fact it is not dissimilar to the modern day limitations of tweeting. If I have too much to say, I use both sides of the vertical divider, which means the card has to be placed in an envelope. My writing often starts out expansive and decreases to tiny as the space diminishes, with afterthoughts sliding up the sides like marching ants.

For Australian artists of the pre-digital age, art postcards were objects of yearning -- images of a culture lodged far away, in museums across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. For those who had made the pilgrimage to these places, they became souvenirs.

If you look at photos of artists’ studios there are usually a few postcards in there somewhere, thumbtacked or taped to a wall, beside a doorjamb or next to a light switch.

The size of a postcard is set by the maximum dimensions for the standard postal charge. They fit in the pocket or can be used as a bookmark. ‘Postcard-sized’ has become an informal unit of measure. The image on the card can change over time, from exposure to light, and accrete a patina of dirt and damage. After a while, whether I have actually seen the original painting reproduced on the card becomes less important.

The other week I went through the postcard box again and chose six cards to write about in this essay. On another week I might have made a completely different selection.

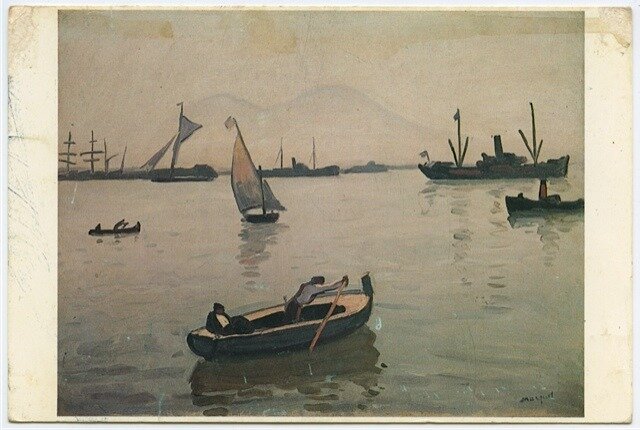

Albert Marquet (1875-1947)

Naples 1909 oil on canvas

Johannesburg Art Gallery

Albert Marquet is generally placed with the Fauves of the early 20th Century -- Derain, Dufy and others. However, by 1909, he was moving away from brightly-hued Fauvist interpretations of landscape, to a more naturalistic use of colour, in this case, the luminous haze of the Bay of Naples. Marquet often painted ports, Tangier, Le Havre, Amsterdam; but I think the series he did on two trips to Naples before 1910 are the acme of his depictions of water and the life on it. They have an exuberant energy about them. Marquet often put transient things into his pictures: pedestrians in a hurry, boats on the move. His paintings are about what happened on a particular day.

Arriving in a new port, Marquet and his wife would take pains to find a hotel room with a busy scene to be had from its window or balcony. Given its low perspective however, I think this picture was done at an easel, close to the shore. Marquet painted quickly, always from life, ‘alla prima’, with a thin creamy impasto.

In 1986, I actually visited and swam out across the Bay of Naples, from close to where Marquet would have painted. It was a summer day and the outline of Vesuvius looked much as it does in the painting. People were sunbaking, eating precariously-balanced picnics on the jagged rocks of the shore, listening to radios, but no-one was swimming. My girlfriend and I jumped in and crawled out through the none-too-clean harbour for a few hundred metres, then trod water in the middle of the bay. A rowboat, piloted by shirtless teenage boys paddled nearby. They called out to us and we looked up. One of the boys was standing up in the boat, making it tip towards us, holding, cupped in his hand, his erection. They rowed off laughing.

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) Portrait of Don Ramon Satue 1823

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The portrait by Goya was stuck for years above my carpentry workbench. This bench is where I sand off paintings that I don’t like any more, so the man’s contemptuous look was appropriate. Goya’s sitter is so insouciant and self-assured, at home in his own soft skin. It has recently been discovered that this image of Don Ramon Satue, a judge, was painted on top of another portrait -- a medalled military man, perhaps French, Napoleonic. It was probably politic of Goya to cover it with the portrait of a Spaniard.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

Limestone Cliffs on the Island of Rugen 1818

90 X 71 cm Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur, Switzerland

When the German writer Heinrich von Kleist first saw Friedrich’s painting Monk by the Sea, he said that it felt like his eyelids had been cut off. It was a similar revelation for me when I first some Friedrich paintings in real life, in the 70s. Previously I had thought them a bit kitsch.

This painting of a ravine between cliffs by the sea is like a scene from an 18th century novel. It was painted just after Friedrich’s honeymoon to that region. I jokingly call it ‘where’s the ball gone’ but in fact I‘m sure the woman in the red dress has lost her bonnet, blown down between the cliffs and the man crouched on the grass, dressed in blue, is contemplating its retrieval. The third figure, a male in a floppy hat, seems disconnected from the small drama to his left and stares out to sea watching the two white sails. The composition is a sort of tunnel, the ocean, gestalt-like, could be a mountain if the picture were to be inverted.

The figures in Friedrich’s art nearly always stare away from the viewer into the world of the painting which seems to have its own inner glow.

After losing his mother early, Friedrich, aged thirteen, saw his younger brother drown, falling through the ice on a lake. He had a reputation, later in life, for being a melancholic loner. Yet there is a contemporary account from his years in Dresden, round 1808, that says he was good company, humorous and kind. It relates how the artist used to let the local children come into his studio to watch him paint. One little girl kept asking him to give her a picture, and so he gave her some of his pencil drawings. One day he asked her what she did with them and she replied that she used them ‘to wrap her things in’.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) La Folle 72 X 58 cms Musée des Beaux Arts, Lyon

After his mental breakdown in 1819, Géricault painted ten studies of people with different types of madness. He apparently gifted them to a Doctor Georget, who had cared for him. It was a time when the French were at the forefront of an effort to improve the treatment of the mentally ill. Five of the portraits in this series have been lost, but five were discovered in an attic in Baden Baden, forty years after they were painted. They were amongst the artist’s last oil paintings. This portrait (sometimes entitled, Monomania of Envy and The Hyena) is so direct; free from any anxiety about style or the desire to please either the viewer or the sitter. Those fierce red-rimmed eyes, peering sideways, are difficult to forget.

Géricault, famous for his dramatic canvas, ‘Raft of the Medusa’, died young as the result of three riding accidents. He was fascinated by the macabre. Near the end of his final illness he had the surgeons set up a mirror so that he could observe them excising a malignant tumour from the base of his spine. He claimed that viewing his own anatomy helped him cope with the pain.

Ghirlandaio (1449-1494) Portrait d’un viellard et de son petit-fils

Musee de Louvre, Paris

I know little about Ghirlandaio, but I think this painting of an old man and his grandson is one of the great double portraits. The child, his vision unpolluted, sees only a familiar kindness in the face of his grandfather. The man’s nose is deformed with a growth, Rhynophyma, and there are thick black hairs sprouting from his forehead and down the bridge of his nose. It looks almost as if someone has hacked lines into the paint with a knife, such is their jagged proliferation. There is a melancholy smile of appreciation on the face of the old man, as though he fears that soon, under the influence of peers, his grandson will revile him; or that soon he himself will die and never see this boy grow into a man.

References:

Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer Theodore Gericault Phaidon 2010

Marcelle Marquet Marquet – Travels International Art Books Lausanne 1969

Gail Levin The Complete Watercolours of Edward Hopper Whitney Museum of American Art New York 2001

William Vaughan, Helmut Borsch-Supan, Hans Joachim Neidhardt

Caspar David Friedrich 1774-1840 Romantic Landscape Painting in Dresden

The Tate Gallery 1972

Tom Carment 2014 www.tomcarment.com