The post-war arcade off Cowra's main street where for 35 years Olive Cotton had rented her two-room photographic studio was up for demolition. Developers were building a bigger and better one, they said; and in recognition of Olive's status as a 'living national treasure' had offered her some space in the new one, rent free. She declined. She hadn't been in there much recently - at 85 her printing days were over and standing up for any length of time irritated her leg ulcers. I drove up from Sydney with her daughter, Sally McInerney, to help clear it out.

Sally decided that we should do most of the initial sorting without Olive there, in case she found it too overwhelming or sad. This was fine with Olive who seemed on the surface quite unsentimental about the whole event - happy to leave it in Sally's hands. Olive's husband Ross too, seemed only concerned that I salvage as much of the re-usable infrastructure as I could - shelves, taps etc. - before the demolishers smashed it all, wasted it. The setting up of the dark room and office 35 years ago was still fresh in his memory and he was especially proud of the way he'd built the shelves. Sally was in fact the one who seemed to me most saddened and anxious.

We borrowed a friend's van and drove the twenty kilometres to town from Koorawatha and parked it near the back entrance to the arcade, one of those spacious country town carparks. The first thing I did was take down the sign hanging from a chain by the door, painted by a signwriter in imitation of Olive's youthful signature. 'Closed for Business', I thought. The bulldozers were already busy shoving piles of bricks about immediately through the wall and Sally and I had to shout to hear each other. We opened up the door and stood there for a while. On the left hand side where you came in was a browned grey-green caneite panel with a selection of Olive's commercial work stuck onto it with large rusty drawing pins - portraits of children and adults from the 70's, with hair spruced up, brylcreemed and permed, long collars and wide ties, ruffle-necked and empire-line dresses. On the other walls were pinned her non-commissioned prints, some well known, some I'd never seen before - her ex husband Max Dupain crouching down photographing a model on the Cronulla sandhills (a play within a play), clouds in the water, a burning log, a tunnel of trees at night. At waist height all around the walls ran the green laminated shelf which Ross had built in the 50's, as over-engineered as the Harbour Bridge and held together with lots of long screws. I decided against its removal - there was too much else to do.

Stuffed behind all the diagonal shelf brackets were stacks of neatly-folded wrapping papers and envelopes of photographic paper (some still containing unused sheets which were up to twenty years old). I wondered whether this obsessive recycling was a hangover from wartime paper shortages or just sensible country town economising. (Like a woman I know who washes and stores the gladwrap from the supermarket meat). In amongst all this brown, buff and yellow paper and neatly-tied skeins of string were lots of Olive's commercial prints: children, weddings and classrooms. Sally told me how much Olive used to dread doing weddings; one mistake and that was it - you couldn't ask them to do it all again. Some of the child portraits were really good, blurring the distinction between the 'bread and butter' work and the 'artistic' prints. Bearing in mind that around the time she did these (the 60's and 70's) Olive had had her entry rejected from the photographic section of the Royal Easter Show Art Prize (she said philosophically to Sally that she guessed 'fashions must have changed'). We came across a package of about thirty photos of Sally's wedding to her first husband Geoffrey Lehmann - Sally drifting winsomely through crowded rooms in an embroidered Indian dress. 'But Olive didn't take photos like this at our wedding. These couldn't be hers.' She finally remembered that John Firth-Smith had the camera that day and being a very tall man the camera angles could never have been Olive's.

I left her to sort through these old memories and piles of negatives and got to work with spanner and screwdriver in the darkroom next door. I dismantled a giant old enlarger of the type made for glass plates and probably not used for decades. I think Sally said it had come from Max's wartime studios in the city and was ancient even then. Every so often Sally would call from the next room and show me a puzzling object or exciting discovery. She found a couple of prints she'd never seen before, two nocturnes - a tree stump on fire and a galaxy of moths at the kitchen window. Some old copies of Sydney Ure-Smith's Australian Society of Artists Annuals from the 40's turned up. In small print on the third page I read that Olive was the photographer of all the paintings and sculptures in them. There was a handwritten dedication in one, which read: 'To Olive, for all her hard work' signed by Sidney.

Later that evening by the fireplace at 'Iambi' I pulled them out and asked Olive if she remembered doing those jobs. Her recollections were surprisingly clear; of how she photographed each piece and what she thought of different artists: how she'd used a sheet of ground glass behind a particular sculpture, how she found Francis Lymburner self-obsessed and Douglas Annand very nice. (Sally told me that in the 40's Francis Lymburner had a studio in the same building as Max Dupain's and one afternoon invited Olive in for tea. He offered her gin but she said just tea was fine. She felt a bit uncomfortable and when a big cat jumped into her lap she let it stay there, despite a dislike of cats, and stroked it. Francis stared at her for a while, then murmured, 'Lucky cat'.)

Sally and I kept sorting the studio throughout the afternoon and began to load the van with things to keep and store. Ross brought Olive in around three-thirty. She looked about her old studio with calm interest (like that of a visitor I thought) and thanked us for what we were doing. I showed her a pile of odd-shaped stencils (some of them stuck onto wire like fly swats) and asked her what they were for. She replied that she'd made them especially to block out parts of a photo she was printing. One, a piece of old stocking stretched across a cardboard window, was for 'softening things'. She told me to keep a big sheet of highly-polished stainless steel - she used to heat it up and use it for glazing prints on cloth-based paper, she said. The bulldozers had stopped, although we'd hardly noticed, and stood frozen in the rubble as we walked in and out to the van. When we'd finished we shut the door for the last time and took a short cut across the car park to a local cafe to join Olive and Ross for tea. I felt a bit disoriented - a feeling Olive must have often had on leaving the studio after a long session of printing. I felt like I'd stepped out of daytime cinema - a black and white classic with a tearful ending. Some kids on their BMX's crossed our path, yelling at each other on their way home from school sport. There was a stillness of approaching evening in the sky flecked with high cloud and a flock of galahs was squawking and wheeling about above the caravan park by the river.

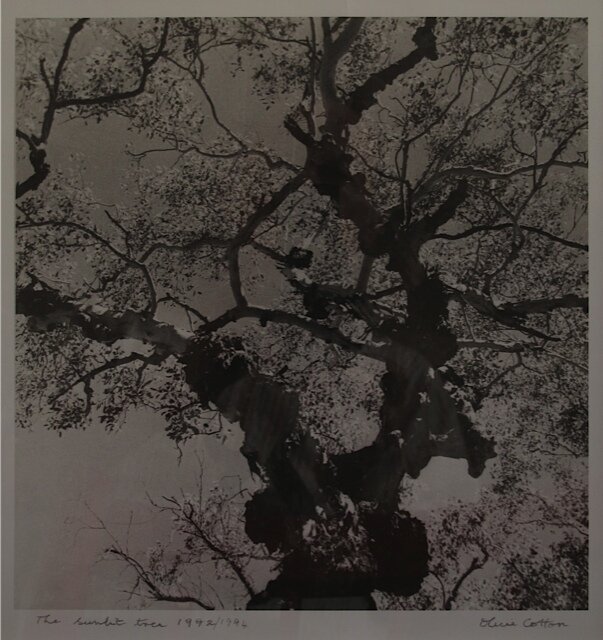

The next day Olive gave me a print of a gum tree against the sky. The signature is unsteady and there are white dust hairs on the darks, but I like it for that.