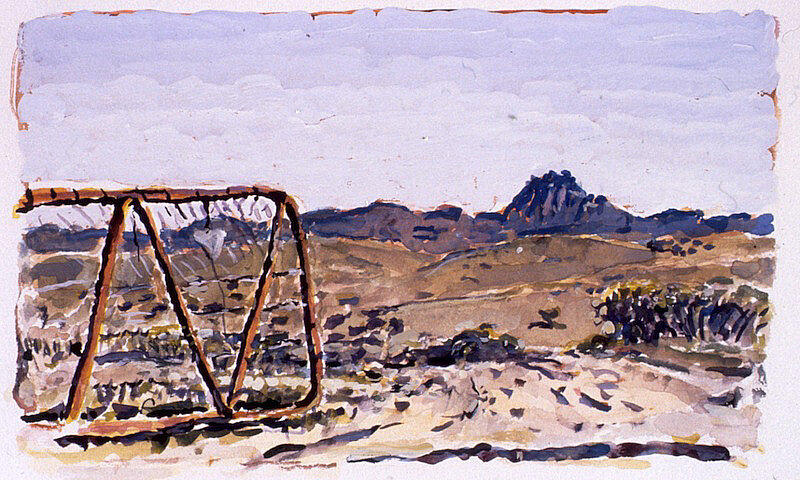

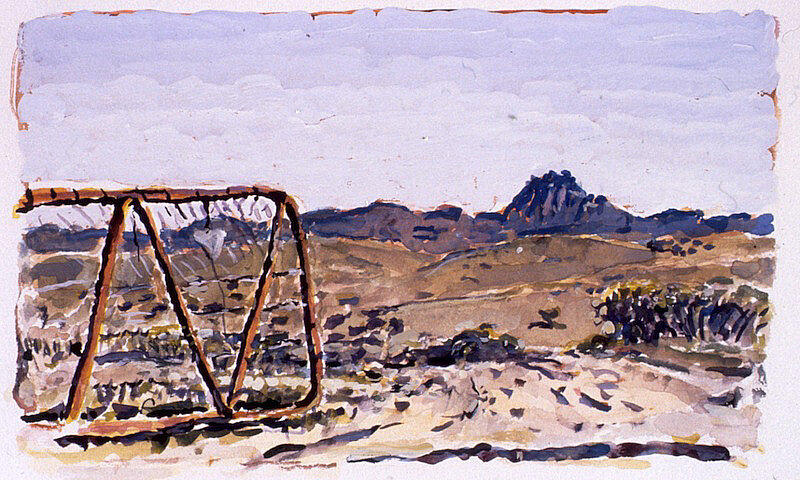

Gate, Angorichina SA

Armed with a book called 'Free Camping in Australia' and towing a 6 x 4 foot box trailer behind our Commodore VH, my partner Jan and our three children – Felix 10, Fenn 8, and Matilda 4 – departed Sydney in October 2002. We headed west, slowly. Jan's parents in Perth were celebrating fifty years of marriage just after Christmas and had promised (jokingly) to stay together until we got there.

It took us 28 days to reach Perth, although I didn't feel our crossing had properly ended until a few weeks later when we all sat sheltering from the wind in a limestone cave on the westernmost part of Rottnest Island.

In the weeks before our departure, the navy blue and slightly rusty box trailer, bought from an advertisement in Trading Post, took up most of my energies (and the space in our small Darlinghurst backyard). I used all the timber that I'd hoarded for years to extend its height and make a sloping lid for it –lockable, waterproof, dustproof and painted in gloss white enamel. It looked a bit like a big dog kennel. I even used some lengths of 150 year old cedar given to me by my friend Euan. I primed up dozens of different sized wooden panels to paint on. Jan bought an old Super 8 camera and hard-covered journals for the boys.

When we took the kids out of school some of the parents said they envied us: 'It would be so great to do what you're doing', they said. And yes, it was great. However there were times when the children really missed their playmates back in Sydney – the brief friendships struck up in playgrounds and van parks weren't all that satisfying. And there were times when Jan and I felt like Sherpas to our children: the evenings when we tried to pitch camp and cook dinner in howling dusty winds, the mornings when the poured milk never hit the Weet-Bix but blew off sideways towards the horizon, and the endless replays of 'Barbie Girl' by Aqua demanded by Matilda to keep her happy on the long drive across the Nullarbor. Why did I ever buy that tape?

12/10/02 Gooloogong

Our first night of camping was on a stock route a few kilometres west of Gooloogong. Inside our tent I listened to a crackling radio by the light of a battery lamp, swatting bugs. Felix and Fenn were still chatting in their tent. The moon was half full, some angel wings of cloud passing by it. We’d set up camp a bit too late, as Jan wanted to see the Japanese Gardens in Cowra – described by Fenn as a good place 'for calm and condensation'. I'd also stopped to buy a longneck of beer from a pub at Mandurama – a young friendly girl serving, a bit 'Goth', V8 car racing at Bathurst on the TV, two men looking up, mesmerised, at the cars’ skirts skimming the bitumen.

As we struggled to put up our tents and cook before it got dark, someone started shooting at kangaroos or rabbits in the paddock opposite; random popping for about half an hour, a bit too close. Matilda's wheels fell off as she sat on a fold-up stool at the card table, having waited too long for dinner. 'I want to watch TV!' she shouted over her bowl of chops, beans and potatoes. Then, between sobs, she hummed the theme music from The Simpsons. The shooting stopped and it was getting dark so I tried to light the mantle of our gas lamp. I hadn't properly tightened some new brass fittings on the neck and a whoosh of flames came out just above the bottle. I panicked. Jan calmly smothered the fire with her beloved woollen picnic blanket (a twenty-first birthday present from 1981). It’s now a charred and holey relic.

14/10/02 Hillston (Western NSW)

I heard about the nightclub bombing in Bali on my campsite radio in our caravan park near the banks of the Lachlan. Everyone else had fallen asleep in their tents, and bugs tapping against my electric lamp. Sad faraway news.

Previously, after our meal, we had all walked down the wide main street of the town to buy an ice cream. First, we'd walked past the 'Exie's' club (so it's named on the town map) with its neat garden of roses and sweet peas, two men sitting down to a meal in the bright dining room, Brylcreemed bow-waves in their thinning hair. The sign outside explained that the club was in no way affiliated with the RSL. On the nearby war memorial I counted that about sixty names from Hillston, men who’d been killed in the First World War, and sixteen from the Second World War – a lot of death, I thought, for a quiet place like this.

The shops we passed were cavernous and sparsely stocked (compared to Sydney) except for the crammed agricultural supplies store which had a sign saying: 'I'm your bloke! Big enough to have what you want, small enough to care!'

We made our way down to an ancient Milk Bar called 'The Golden Gate' which had been run by Bill Morgan and his sister for nearly sixty years. It was still open well after dark, the V8 races from Bathurst growling from a TV in the corner. Mr Morgan, a tall and aged man, sat behind a glass and chrome counter where bobby pins, styptic pencils and chocolate bars were on display. He shuffled out to serve us and wouldn't let the children take their own ice-creams from the slide-top freezer provided by the ice-cream manufacturer (a sign: 'no self-service!' in a shaky hand was taped to the perspex). When Felix and Fenn ummed and erred over their choice he got a bit annoyed and when Matilda coughed in his direction he stepped quickly backwards – 'Don't let her give me a cold!'.

14/10/02 Balranald Caravan Park

A group of grey nomads had set up a kraal of mobile homes and caravans behind us, all facing in on each other. The nearest van had an 'I love Country Music' sticker on its side and a movement sensitive security lamp above the door whose sudden high wattage glare made me drop my toothbrush in surprise.

In the amenities block, a man in blue boxer shorts stood beside me at the basins and struck up conversation. I’d seen him coming out of the ‘Country Music’ van. He'd finished combing his dyed black hair was scraping away at his chin with an old-fashioned safety razor. Without turning his head, but looking at me in the mirror, he said, 'Bad business in Bali!’ Then he stopped shaving, stared at me directly, and waggled his soapy razor up and down, ‘Not just Bali. We'll be next! A well placed bomb in the Latrobe valley would cut off the whole of Victoria's power supply. They could do the same at Wallerawang, and blow up the dams too. You wait and see!'

15/10/02 To Lake Mungo

Bulldust had started to infiltrate everything we owned, the sheets, the sleeping bags, the tents and the cooking gear. We wiped out our cabin and left the Balranald Caravan Park by 9.30am. The man in the office assured us that the gravel road to Lake Mungo was good – ‘Just been graded’ – but we found it very rough, with shuddering corrugations. About halfway through the one hundred kilometres of dirt I felt the trailer sway and then heard a slapping sound of loose rubber hitting metal. I stopped in the 35 degree heat, and saw that a long flap had peeled off our driver’s side trailer tyre. Jan and I unpacked all the stuff from the back of the station wagon and retrieved the spare wheel and tools. I jacked the trailer up and pulled off the damaged wheel, but when I went to slide on our Commodore’s spare tyre it refused to go, the studs didn’t fit in the holes – it was a mismatch. I knelt in the dirt, sweating, and cursing myself. Before our departure, in Sydney, I’d asked a well-travelled friend if an 1982 model Commodore tyre would fit our trailer. He’d looked at trailer wheel closely, squinting, and replied, with authority, ‘They’ll match.’ Now I cursed my laziness – I should have made sure myself. My friend knew a lot about sailing boats but not much about cars.

I located a mallee stump thirty meters off the road and left the trailer sitting on that, with a sign in charcoal taped on which read: COMING BACK SOON.

I unhooked the tow bar and strapped the wrecked tyre on the roof, along with anything else we might need from the trailer. Matilda let out a cheer as we hit the road again, but the boys, who’d been reading their books all through the tyre crisis, just looked up briefly before lowering their eyes again. Keeping them supplied with books, we joked, was as crucial to our journey as putting petrol in the tank. Meanwhile, I was making plans, figuring out what I had to do: if I dropped Jan and the kids at Lake Mungo, I could drive on 110 kilometres to Mildura for a new tyre then come back and drive a further 45 kilometres down the Balranald road from Mungo and change it. It was a rather dismal prospect.

Two kilometres towards Mungo I spotted the roof of a shed above some bushes to the right of the road, and said to Jan, ‘Let’s check this out.’ As we turned in I saw an abandoned truck and a group of corrugated iron sheds and some refrigerated shipping containers. Almost as soon as we came to a stop a white Toyota twin cab ute with a long UHF radio aerial arrived behind us and halted in a cloud of dust. A stocky bloke who appeared to be in his early thirties got out and walked stiffly towards me, followed by two dogs. He held out his hand in introduction – ‘Nathan.’ He h and Peaced on a cowboy-shaped hat, his skin was weather-blasted and he wore unusual thick oval glasses, which made me think, incongruously, of Pierre in Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

I explained our problem, and he replied, ‘Yep, saw the trailer. I think we can help you.’

Meanwhile another big ute had pulled up behind his, and Nathan’s mate Dallas got out. He was a giant, well over six foot tall, with a white hat and orange reflective sunglasses. Nathan explained that this property was called Turlee. He lived about five kilometres away and where we’d pulled in was his parents’ place.

We followed him to a shed – red dust on the upper edge of everything, rows of old metal lockers, doors hanging open, with tools and pipe sections in them. To the west Nathan pointed out a two big container freezers, to the west and south-west. ‘That one’s for ‘roos and the other’s for rabbits,’ he explained. Nathan said that due to the dry weather, lots of ‘roos had been coming down from the Lake Mungo National Park.

‘We’ve been shooting 300 a night but have to leave them to rot because the abattoir’s oversupplied.’

He also said that ‘Mungo Man’ (discovered in 1974 and dated at 42,000 years – at the time the oldest human remains found in Australia) was found on his property, at which point Dallas corrected him: ‘Not really your land.’

‘Well yeah, I lease it back from the government until they decide which mob of blackfellas to give it to.’

Nathan had done an apprenticeship in butchery but then returned to the land. His slaughtering shed was impressive – three metres square.

While Nathan was talking, Matilda got out of the car and was soon playing in the red dirt with the oldest kelpie, who’d probably never got so much attention. Among all the bleached greys, rust and red ochre dirt her purple summer frock stood out.

Lucky for us there was a hillock of old car wheels and tyres heaped against one side of the shed. We poked a screwdriver through the bolt holes in my wheel rim to see if any matched. Dallas threw a likely wheel, from a late 1950s, FC Holden, into the back of Nathan’s truck and we charged back effortlessly over all the corrugations to where the forlorn trailer stood. Not bothering with a jack, Dallas stood with his back to the trailer and lifted it up off the mallee root while Nathan pushed on the tyre we’d found in the shed. It fitted. He towed the trailer back to the shed at 100km/hour while I looked around nervously to see it was still there. Dallas found us another tyre and rim for our spare and they tied it onto the triangular part of the trailer with truckie’s hitches. I paid them with three fifty dollar notes and we were all happy. They’d saved me a long drive into Mildura and it was lucky for us that they’d been doing their water run just as we pulled in. Throughout this small drama the two boys had stayed in the car, reading their books, and after we arrived at Mungo wrote in their journals that today we’d gone into a ‘Tyre shop’ to get our wheel fixed. Matilda begged us to go back to Turlee and play with the dogs again.

We stayed a week at with my friends Andrew Nicholson, Helen and Geoff Mills at adjacent sheep stations, Middleback and Myola, between Iron Knob and Whyalla –places I would visit to regularly to paint, once or twice a year. This was the first time I'd brought the whole family there since Felix was a baby.

24/10/02 Middleback

Near the Shearers’ kitchen there’s a small building made of tin and wood with a steep-pitched roof and a chimney. The Nicholsons must have bought a job lot of silver paint about twenty years ago, for all the sheds and out-buildings were painted with it, the silver corrugations of tin dusted with soft lines of red dirt. This small structure by the kitchen is called Mort’s Shed, and still contains the remnants of an old man’s life: a ticking horse hair mattress, some scraps of paper with horses’ names on them, a broken dresser, some cream-coloured crockery. Mort was a well-loved, functioning alcoholic, who lived alone there for years and did jobs on Middleback Station. A tall gum tree grows beside Mort’s Shed, the biggest one for miles around, and unusual in this low, flat landscape of myall trees and saltbush.

Nico told me that, long before Mort, his grandfather, Andrew Nicolson, had lived there as a young man. He’d planted that tree beside a couple of flat rocks where he’d stand to take his morning shower under a canvas bag of water. The sapling had flourished in the run-off.

The boys rose late and explored the shearing sheds, then rode some bikes down the dirt track to Two-Mile Paddock where I’d been painting. Fenn got a flat, a three-cornered jack in his tyre, so he helped me pack up my painting gear and I gave him a ride home in Nico’s ute. I told him how the older Nicolsons would attach a short length of watch chain to the forks of their bikes, to knock the burrs off before they dug in.

25/10/02 Myola SA

We went for a picnic up into the low ironstone-scattered hills eight kilometres behind Myola homestead. The wind was gusting randomly and it felt like rain was coming. Geoff and Helen have left a trailer loaded with a water tank on the track up to the picnic spot, near a fallen windmill and the crumbled, dry-stone surrounds of a well. Geoff said that there’s an underground stream nearby, and that his father could divine for water. He only did it on his own land, not for anyone else. I told them how I'd been shown how to divine when I was Felix's age and reckoned at the time that I had the 'gift'; but I hadn't tried it since then.

After lunch, while Jan and the boys scrabbled for rocks and Matilda played with the working dogs, I suggested to Geoff that we try divining for the stream he'd mentioned earlier. I needed a U-shaped piece of fencing wire as my divining rod – that was what I had been taught to use – and so I searched the fenceline until I found a suitable discarded length, about two foot long. It was badly kinked, but without pliers there wasn't much I could do about that. Slowly I started pacing around with the rough U held up against my chest, gripping the two inward turns of wire with my fist and thumbs. Geoff walked nearby holding out a forked stick. The voice of Yoda from Star Wars kept going through my head, 'Feel the force, just feel the force...' which made me laugh. I didn't feel the wire move at all near the well where Geoff said the stream should be, but about ten metres away to the west of there and again on the track near where Matilda was playing with the dogs, the wire felt like it was being tugged strongly downwards.

And yet I wasn't quite convinced that my ability to divine for water had been retained after all these years - perhaps a sudden wind gust had disturbed my grip.

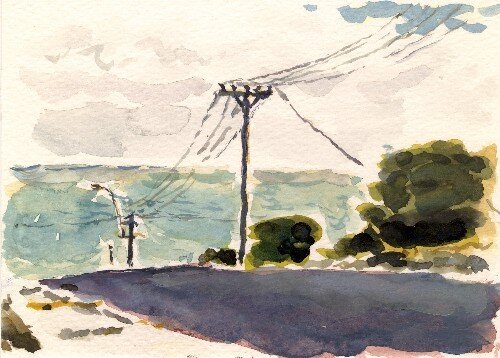

29/10/02 To Pildappa Rock

The rail line that goes west from the steel works at Whyalla to the iron ore mines runs almost dead straight as far as the eye can see through dry plains of saltbush. I once found a twenty dollar note flapping on the sleepers, halfway to Iron Knob. Geoff once found a watermelon growing by the line. Ripe and delicious, he said. You don't see many cars on that long stretch of road and so you get into the habit of greeting passing drivers by raising the forefinger of one hand from the steering wheel.

When we departed Myola station and left the Iron Knob road to re-join the highway – Port Augusta to Kimba – I raised my finger to greet the first passing vehicle and the driver returned it with an emphatic 'up yours' gesture out the window.

Despite consciously telling myself not to worry about it – we were back on a the main highway after all – I felt upset.

'Why are people so aggressive?' I asked Jan, rhetorically.

It made me think of the beheaded kangaroo we'd seen the previous day, stuck by someone onto a fencepost beside the ore line. Helen Mills says that the carrion eaters don't touch them when they're vertical like that and that these ‘trophies’ end up almost embalmed onto the fence posts. She guesses that the joke, if you can call it that, is to get passing drivers to hit their brakes, thinking there’s a ‘roo about to cross.

Helen became so incensed by their re-occurrence of this macabre practice that she used to stop the car on the way in to Whyalla and use a stick to heave the dead animals off the posts. One time she ripped the post right out of the ground.

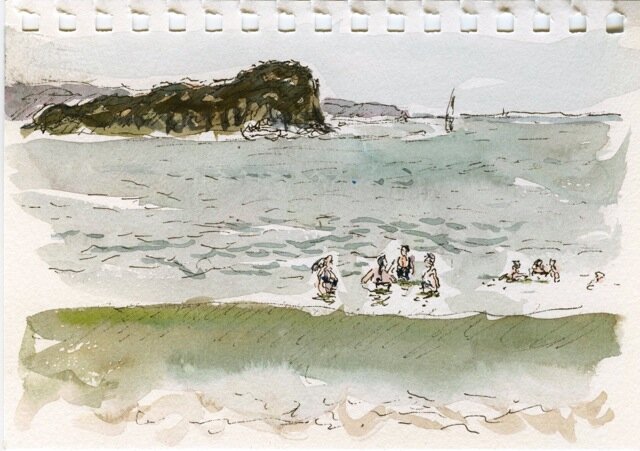

30/10/02 Fowlers Bay

'Have you ever made really big pancakes? My mum makes pancakes shaped like a squid!' Fenn said this to a boy called Jake, on the swings in our caravan park. Jake was a weathered and skinny kid, with scabbed knees and a lot of energy. The boys had made friends with him, and so I followed them out to the end of the jetty where they wanted to play, in case they fell off. The windswept waters of the Great Australian Bight gain depth slowly here, and so the jetty is a long one. Jake’s Dad was called Ots and he walked with a hunch wearing a pair of old steel-toed boots without socks, the metal showing through the worn leather. He told me he’d like to go everywhere barefoot, but, because he’d had his knees broken a while ago, he has to wear these boots. They help him walk. He lived in a caravan with his girlfriend and their three kids.

Ots referred to himself in the third person, narrating his fishing technique as we stood behind him: ‘Ots casts in the opposite direction’. He cast his hand line expertly towards the south west, a long way out. It was beautiful out there at the end of the wharf in the late afternoon, but I felt anxious. The boys were jumping around along the unfenced edge of the timbers skipping over and around the fishing rods, buckets and dogs. The wharf timbers were stained with splats of squid ink.

When we first arrived at Fowlers Bay there was a refrigerated truck parked at the beginning of the wharf and a smaller Daihatsu rattling back and forth along the loose timbers, bringing fish from a rusty trawler tied up at the end, twenty tons of shark, destined for Melbourne (we were told). Jan talked to the boat’s skipper, Jeff, at the end of the pier and in the evening he brought a bundle of filleted, fresh shark around to our caravan. I think he was a bit disappointed to see me there. We were still eating it at our next campsite on the Nullarbor, near Balladonia, and it remained delicious, after three days on ice in our esky.

When I said goodbye to Ots, he said it was a shame I hadn’t talked to his ‘old lady’ about art. ‘She’s a painter too – but different stuff to you. Fairies.’ He took me over to their caravan where she spent most of her time looking after their one-and-half year old and a new baby. ‘I’ve been too busy lately,’ she said softly, looking up through her long fringe; ‘but I can feel some pictures building up inside me.’

Further down the highway, at the border crossing, we had to get rid of all our cardboard fruit boxes, filled my painting panels and clothes, and peel the skin off our unwashed potatoes.

5/11/02 Cocklebiddy (halfway across the Nullarbor )

A bikie-looking bloke insisted on giving us 'driveway service' and filled us up with Super (the most expensive on our east-west crossing).

'Where yer from?'

'Sydney.'

'Just around the corner, eh.'

'But my wife was born in Kalgoorlie,' I said, pointing to the inside of the car. 'We're headed there to pay homage.'

The man dropped his voice to a whisper: 'Let me give you some advice buddy. When you get to Kalgoorlie, leave the wife and kids at home and take yourself off to one of them tittie shows.'

Inside the service station office there were swirls of red dirt amongst the ripped old tyres and scattered tools on the workshop floor. I handed over my credit card. 'That'll be $69.60 buddy – special discount. And what shall I add on for the tip?' He winked.

There was a plump blonde girl standing in the doorway behind the counter. 'When are we going for a ride?' she asked him. 'I'll take yer tonight, OK? We'll go for a ride tonight,' said the man, out the corner of his mouth, slamming the till shut. She stood there, hands on hips, a resigned look on her face.

We drove off down the straight flat road. 'I wish you'd stop telling people I was born in Kalgoorlie,' said Jan; 'You only do it to give yourself kudos with the locals'.

7/11/02 Kalgoorlie

We returned from a morning of Goldfields tourism to the sun-blasted Golden Village Caravan Park (no stars, no lawns). We had been taken on the underground tour by a retired miner called Les, barrel-shaped, with leathery, thin arms. His first mining job was with asbestos at Wittenoom. ‘I sucked in lots of dust, I smoked a lot of cigarettes, coughed a lot, and watered it down with plenty of beer,’ he told us. He showed us how to tap the roof of an area just blasted, with a crow bar, to see if it’s ‘drummy’. He asked Jan to demonstrate the pneumatic air drill, a task she did with aplomb. Then we tried gold-panning in nicely faked creek – a couple of pools of muddy warm water. We became obsessed, shoulders burning in the sun.

To one side of our cabin at the Golden Village, a man in a singlet was watering his neat collection of garden gnomes and pot plants. The Eagles were blasting out from the caravan next door. 'Revenge,' said Jan. We'd been pretty noisy ourselves before we'd gone out that morning. A lot of the men who lived here probably worked twelve hour shifts, often at night.

During the worst heat of the afternoon I went out on my bike and did some drawing near the railway line while the boys did maths and wrote up their journals beneath the rattling air conditioner. When we'd all finished I took them to the 'pool', which was really just a part of the owners' 1970’s brick bungalow, separated by a screen of ochre shade cloth. You could see their brown silhouettes, sitting around having a few beers. A boogie board and a few purple foam noodles were floating on the water when we arrived, so the boys invented a battle game, sitting on them, each trying to reach the opponent's side. I didn't feel very comfortable about the proximity of the brothers' excited yelping to this domestic scene. After five minutes a gate in the shade cloth opened and a solid woman came out clutching a toddler in tight T-shirt and disposable nappy. 'You can't play with that boogie board, it's Brandon's!' Ants had crawled out through the cracks in the concrete and has started nipping the tender skin between my toes. I broke short the boys' water sports and hustled them back to the cabin.

Felix asked if he could go out for a cycle around the van park. The previous night he'd done circuits of the park with a bunch of boys, racing past the vans and cabins, shooting the speed bumps. We said alright, but told him to be careful, look out for cars. Fifteen minutes passed and we were just starting to worry about him when he returned on foot, an Aboriginal girl twenty metres behind him, riding his bike. She was very dark-skinned, with thick tousled hair and she rode the bike slowly, standing on the pedals because the seat was too high for her. She told us she was bored, that her brother Calvin was in their van playing games. Her name was Rose and she was eight. I'd passed her earlier in the day near the camp kitchen. She'd smiled shyly and waved at Fenn and me. There was a recent scar, which it looked a bit infected, across the bridge of her nose. She explained that it was Calvin's returning boomerang that had done it, an accident. It had really hurt.

She played for a bit outside our cabin as I sat on the stoop peeling potatoes for our dinner. 'Can I go and get my brother?' she asked, and a minute later she came back with Calvin, who had 'Calvin' stencilled in white across the back of his black T-shirt. He settled down with Felix and Fenn on the bottom bunk, all looking at a Simpsons comic book, the big one we'd bought in Whyalla, with the brothers taking it in turns to read aloud. Calvin said he could only read slowly and told Felix he was a bit embarrassed about it.

Rose was interested in what I was cooking for dinner (lamb and potato curry) and said she didn't like spicy food but her brother did. She'd been doing painting with Matilda, perched on top of the trailer. She got me to paint an elephant for her, and after I'd done the outline she asked me to 'make it grey'. I showed the girls how to mix a nice grey from equal parts of deep red and deep green. It was a beautiful balmy inland evening with long shadows and warm bands of sunlight, galahs screeching amongst the fiercely pruned gums.

They stayed on for dinner, after first running back to their van with Felix to check if it was alright. 'I love my mum,' said Rose, out of the blue, 'but she won't let me go to the supermarket on my own.' Over the meal Felix and Calvin talked about pocket money and Calvin said that sometimes he gets $50. 'Wow,' said Felix, impressed. But Rose said that's only when they go and see old Aunty Alice and she added that up at 'John's place' where people do lots of drinking they pick up heaps of money off the ground, but that John has Dobermans to 'keep the sniffers away'.

'What are sniffers?' asked Felix.

Calvin didn’t answer, but started talking instead about his uncle who drives them to Perth sometimes 'in five hours, like a racing car driver'.

'Cool,' said Fenn.

After dinner they wanted Jan to walk them back to their van as they said they were a bit frightened. Calvin pointed to one van on the way and said that they'd lived in that one for a while but they'd had to move, it was sort of spooked. He pointed to another van, telling Jan, 'You've got to watch out in this place. The fella in that van over there, he's always looking at me mum.'

We woke up and packed the trailer to drive on to Coolgardie and Southern Cross. It was already hot. Felix kept asking what time it was, because he wanted to go and say goodbye to Calvin and Rose and give them his Simpsons comic. We'd said he couldn't go over too early. He had his disposable camera with him and wanted to take a photo of them. We discouraged him from doing that, saying it was probably a bit intrusive. At 8.15am we let him go, and he sprinted off. Five minutes later he came back, panting from his run, smiling.

'How did you go, Felix?'

'Well, I said goodbye and gave Calvin the comic and I asked if it was OK to take their photo and their mum was really encouraging. She said: Come on! Stand up straight for him.'

We got the photo back a few weeks later: outside a 70s caravan, Calvin, bent over looking down at the open Simpsons comic, Rose looking away from the camera, up in the sky, squinting. I posted it to the caravan park.

10/11/02 Coolgardie to Southern Cross

At Coolgardie, 39 kilometres from Kalgoorlie, we lunched in a park where the grass was luxuriant and green – such a contrast to the dry red landscape around the town. I put my head on the ground and drank eagerly from one of the brass garden taps. There was on old ornate shed in the far corner, built into the boundary fence, with a Chinese style roof. I guessed it may once have sold food to picnickers. I pictured them in their hats and waistcoats fetching hot water for billies and pots of tea. As we left the park I noticed three yellow signs staked into the ground: 'Do not drink from taps - Treated Sewage'.

In the 1880s Coolgardie had 16,000 residents, but now there were only a few hundred. No Kmart or skimpy barmaids here. The city's gold rush past was to be seen in the stately public buildings scattered down the main street, like teeth in a gummy old mouth.

We paid a few dollars to the Tourist Information volunteer and wandered unsupervised through the old courthouse, now a museum. The floorboards creaked as we walked in and out of numerous antechambers filled with exhibits, put together it seems, by different people at different times, mostly the work of enthusiastic amateurs. Red dust had penetrated some of the cabinets in which objects were displayed above red and blue embossed Dymo labels. (I remember my father bought a Dymo machine in the 1960s and soon we'd put labels on everything: desk drawers, a leather camera case, vinyl LP covers, tennis rackets, Globite suitcases.)

There were exhibits about water, how hard it was to get, photos of huge wood-fuelled condensers which de-salinated bore water. One room dealt with transport. A photo showed a family in a sailboat with metal wheels on a dry salt lake.

In the high-ceilinged central chamber there was a great surprise – the Waghorn Bottle Collection. Three long walls were covered by upright cabinets containing thousands of bottles, in all shapes and sizes, the lifelong obsession of May and Frank Waghorn. Each cabinet was backlit through frosted glass, creating a constellation of transparent colour – like jellyfish floating in space. This was the old courtroom, with a mezzanine for the public, and hand-adzed floorboards.

Earlier in the day, halfway from Kalgoorlie, we'd seen a bearded thin Aboriginal man in faded work clothes, riding a ten-speed bike slowly along the highway. As we left the Bottle Museum I saw him again, in the afternoon heat, pushing his bike through the meagre tree shadows.

We asked the Tourist Information lady if there was anywhere nearby where we could possibly swim. 'They're re-filling The Gorge. You could try that. It's just two miles out of town. We all learnt to swim there and then it got drained by the mines.'

The Gorge was a hundred metres of muddy water in a half-full reservoir. At the far end, a black poly pipe held up by a forked stick gushed water down onto a yellow plastic tarp that lay semi-submerged on the bank. The water looked muddy but a man called Brett, who had come by to chat, told us that they were pumping this water from an old open-cut that had flooded when they’d struck an artesian stream. Brett told that he used to be a miner but was now a youth worker in Kalgoorlie. He reassured us that this water had low salinity and was almost good enough to drink. He suggested we sit on the tarp beneath the inlet pipe, ‘It feels great.’

We swam out through the shallow water, all glinting in the afternoon sun to where the pipe gushed. As Brett had said, it was good to sit beneath, like big warm hands massaging your head and shoulders. We wrestled each other for a turn. The mud beneath our feet was soft and red.

When I got back to the car Jan was talking to Brett about Kalgoorlie, the social costs of the 12-hour shift system on mining families – the drinking, the broken marriages and dispirited teenagers and children left behind. On the drive back from the dam Jan imagined that the women out here might go mad, stuck in a hot house looking after three or four kids trying to keep the red dirt out the front door. We passed the smelly carcasses of several kangaroos and nearly added to them when two emus suddenly skimmed past our front bumpers.

We bought some ice-creams and a bottle of Emu Export and headed west along the highway for Southern Cross, 180kms to the west. Felix wanted us to stay there the night, he liked the name. ‘It’s the destination of my dreams’ he declared. But the afternoon shadows were getting long and I’d seen a spot, 80 kilometres away, in our Free Camping book, near a local granite outcrop. The roadside heath we passed through after Coolgardie was burnt, but not a by recent fire – a calligraphy of charcoal with wildflowers blooming underneath. I followed our camping book and turned right 80 kilometres down the highway, Felix frowned as I did so. After that we must have taken the wrong track somewhere, for, after twenty minutes of bumpy driving, we ended up, not at the rock, but in a grove of white-trunked gums with leopard-like spots up their trunks. The ground below was dark and ashy and littered with broken bottles and tin cans. ‘This looks like good terrain to stroll out for a midnight piss,’ said Jan.

We turned around and made our way back to the bitumen highway and turned right. Emerging from the scrub we drove past the first of many vast wheat paddocks, tattered tree lines marking its faraway border.

‘Where are we going now?' asked the kids.

‘We’re going to stay at a caravan park in Southern Cross.’

Felix gave a big fist pump.

4/11/02 Southern Cross, Quairading, Perth

There was a ‘For sale’ sign on the weatherboard teacher’s house. We could have bought it for $44,000. It sat, unfenced, across the road from Quairading High School where Jan’s father, Don, had his first appointment as Principal. The old hall nearby still had a sign, ‘Manual Arts’, screwed to its timbers, just as it had been when Jan was a student here in the late 1960s.

Between the ages of five-and-a-half and eight-and-a-half and Jan lived in this government-owned house in Quairading, a wheatbelt town 160 kilometres east of Perth. She speaks lyrically of that time, comparing it to our own children’s tethered and organised inner-city life. In Quarading she and her sister Helen had the freedom to walk off from the house and play all day in the bush until it got dark. There was a laundry in the backyard, no back fence, and the school was just across the road. The way she described it seemed to me like an Australian version of the school in Alain Fournier’s Les Grand Meaulnes.

Jan rang her father and reported that the teacher’s house was still ‘looking good’ – the only change was that the underside had been bricked in. ‘That means they’ve probably fixed the white-ant eaten piers,’ said Don.

We drove through the town centre, past the Butchers Shop with blue and white check tiles, where Jan remembers being sent to buy ‘four lamb forequarter chops’. We picnicked by the municipal pool, which was closed, and, at 25 metres, half the size of the one in Jan’s memory. A boy had drowned there in the late 1960s, she told us, and people thought he may have choked on a boiled lolly.

The town was unnaturally quiet and we realised later that it was Melbourne Cup Day. Being cut off from the news, we hadn’t realised. The jockey on the winning horse, Media Puzzle, Damien Oliver, was a sentimental favourite – he’d recently lost his jockey brother Jason in a riding accident and his father, a famous jockey, had also been killed on the track.

Our journey west accelerated after the overnight stay in a Southern Cross caravan park. The owner, Grahame, had been showing me a collection of old cameras and his antique scissor-sharpening machine in the office when the boys started tugging at my shirt, in the direction of the door. The children just wanted it to finish now – no more adventures were necessary. They were sick of the wind and the dirt, and were dreaming of the irrigated, green lawns of suburban Perth, the shag-pile carpet in Jan’s parent’s TV room, and of catching afternoon waves on their boogie boards at Watermans Beach on the Indian Ocean.

So we drove on through the day, looking out at the blanched wheat country. Jan, who has a more expert eye than mine, reckoned the crop near Bruce Rock was a lot better than the one at Merriden. Matilda begged to be given another shortbread cream biscuit.

‘You can have one when you’ve counted 39 fence posts’, said Jan.

After that it was on and on to Perth, with the shortbread creams and rice crackers slowly rationed out; over the River Mackie, through Beverley, and York, where Jan’s parents had their first teaching jobs.

Finally we drove down over the scarp into the slivery afternoon light of northern Perth, from where we could view all the suburbs stretched out in the sea haze. The children cheered when they saw the ocean. When we arrived at 27 Arkwell Way, Jan reached over my arms and held her hand down on the horn. People across the road, who’d been edging their lawn, stopped to look up at our bike-topped, dusty travel set up, with its dog kennel trailer. Jan’s parents stepped out from the shadows of their front garage, and Matilda ran up to them, the sea breeze in her hair.