I don’t fish - in fact I haven’t put in a line since I was 15 - but I have some friends who do. I like eating the fish they catch and I respect their singular obsession, but I don’t envy them. On the other hand, the way they go about their fishing is not unlike the way I do my plein-air painting: the selection of site, time, tide and type of weather. The choice of bait, rod, type of rig and when to alter them, combined with the elements of skill, patience, luck and superstition. I can relate strongly to all this. And most of all I like the idea of affectionately returning to a favourite place.

Two or three times a year, Bernard, Steve, Lewis and a few others travel from Perth down to the coast east of Albany, to fish. Bernard is tall and starting to bald, with strong potter’s arms; Steve is curly-haired and athletic and Lewis has a calm solidity about his person - hard to shift off a rock. They are all aged about forty and have been going to this spot together for more than 20 years. The best fishing here is around Easter when the sea salmon usually come in, but when the weather is unpredictable and often foul.

For the week before New Year we went down there with them - Jan, me and our two small boys, Felix and Fenn. It was our second visit.

This story is not really about fish, but they are the reason we were there - seven adults and six children - camped a few hundred metres back from the windblown Southern Sea. Our tents were pitched across the pathways of small marsupials and reptiles that, for nine months of the year, forage undisturbed at the edges of the nearby lagoon. Occasionally a big storm pounds through the sandbar that dams the lagoon and swills it out to sea. This hadn’t happened for a while and the leaf-stained water was almost fresh enough to boil your rice in. We swam in it and filled up buckets to wash our dishes. The sandy bottom of the lagoon was covered with a thin layer of silky mud and receded gradually without rocks or holes so that the kids could paddle in relative safety. A single black swan patrolled the perimeter and a gang of black cockatoos came daily to bash around in the branches of the paperbarks on the other side.

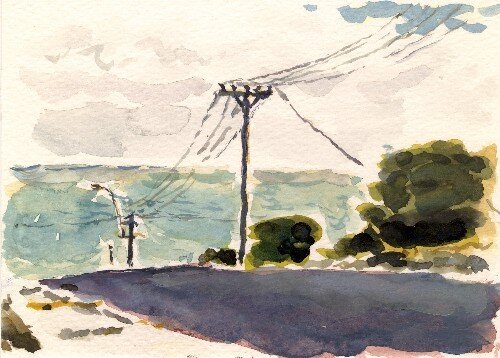

The nearest town is Many Peaks, 15 kilometres away, which has a store where you can buy petrol and glean fishing information from up and down the coast. Some basic food and tinned products are pushed into a corner by rolls of wire, backpack sprays, boxes of lambing rings and such-like. We went there every other day to refill our water containers and buy ice and some more mulies (pilchards) for bait. Most mornings I went out along the windy beach with my gouache or oils in a backpack to join the fishermen. The sand is white and so fine that it squeaks beneath each footfall. The favoured spot is a sloping shore of granite boulders facing east, two kilometres from the tents. The men usually fish from these rocks for three or four hours and almost never come back empty-handed. There also seems to be a perfect accord amongst them, born of long friendship, as to the right time to leave. Quite a few rigs get snagged and lost and they catch a lot of ‘buff bream’, which taste ammoniac and have to be thrown back. The rock pools are full of shellfish, orange corals and lots of crabs. They gut their fish at the edge of these pools, watched by crowds of gulls, who sometimes lose patience and raid the bait. Steve told me that when these rock pools were less silted-up than they are now, a three-foot wobbegong shark would regularly swim in and heave its body over a ridge of rock, through only a few inches of water, to grab the scraps of gut and head. It once took a fish-head right out of his hand.

The first day out there I did a watercolour of the early morning catch - three herring and a bream. The blood around their hook-ripped mouths was a deep cadmium red and their bodies were subtly coloured, like the inside of an abalone shell. Steve had covered them with a sodden newspaper and had lifted it off so that I could paint. After I’d worked at it for half an hour, he was anxious to cover them again.

I walked back along the beach at lunchtime and it was much hotter than before. The sand burned my bare feet. By the time I got halfway up the sandy track between the beach and the lagoon I was sprinting from bush shadow to bush shadow, yelping (the sand here was darker and had absorbed more heat). Miraculously, beside the track, was a pair of old blue thongs. I slipped these on and successfully traversed the gap, and even then, the sand was scalding the sides of my feet. Ten minutes later Lewis came hopping into the camp, swearing that some bastard had nicked his thongs.

The following morning I went out to the rocks again, with thongs in my bag, and this time painted a small panel in oils of Bernard and Steve fishing against a grey morning sky with bands of light occasionally striating the rough sea, and the line of Many Peaks mountain on the horizon. It was very windy. Jan, Jenny (Bernard’s wife) and the kids turned up later and racketed about amongst the rocks. Our youngest boy, Fenn, sat companionably next to me and sang a rambling made-up song until he got bored and ran off again.

A few hundred metres into the bush behind us, Lewis had parked his old Daihatsu truck beside the rusted ruins of a fishing shack (charcoaled graffiti on the fireplace wall read ‘KILL HIPPIS’). We all went back in the truck, lying on the springy old mattress (where Lewis slept at night) in the canvas-covered tray in the dust and diesel fumes, looking out the back at the tall bearded grass trees as we passed by.

The next day, again in Lewis’s truck, we saw a python on the road. We stopped and got out to shoo it into the bush. Steve said that otherwise someone would probably run it over - someone who wasn’t looking, or who didn’t know that pythons aren’t poisonous. From close up it was patterned all over with a shiny camouflage in olive, brown and lemon - military in style, but more ornate. We had trouble getting it to leave the warm dirt but eventually it got the idea and moved slowly away into the scrub like a trickle of water, the sun glinting off its back.

Late the next morning, toward noon, Steve decided to set up his hammock between two trees above the lagoon. He had just lain down in it when he looked over the side and saw another snake. This time it was a big black ‘dugite’ (very poisonous). After a brief conference he decided to kill it - there were too many small children around. He grabbed a spade, crept back toward the snake, raised the spade high, hesitated a moment, chopped at it and missed. It crawled into a clump of grass and hid.

Bernard and Lewis, ran up with another spade and an axe, taking up positions around the clump, waiting for the dugite to emerge. They stood, bodies tensed, holding their weapons slightly raised, like cricketers waiting for a fast bowler.

I was standing well back with Jenny, Jan and the kids, looking at Steve’s bare legs and thonged feet (the other two men had wisely put on shoes and jeans). We began a whispered discussion about snakebite first aid. Jan said that you’re not meant to suck and spit out the venom any more, and Jenny thought that tourniquets were the go. I thought that tourniquets were out.

After five minutes of this anxious stand-off, a curly-haired farmer, camped further along the lagoon, came up to see what was going on. ‘Got a snake mate?’ He asked. He took a quick look and ran back for his .22 rifle. He poked it into the grass then, without hesitation, squinted, aimed and pumped out about five shots, waiting a second or two between each one.

When we were sure the snake was dead, Steve pulled it out of the grass and held it up. It stretched from his shoulder to the ground. We took photos. The farmer’s three blond kids clustered eagerly around, ours held back. It was against the new gun laws for him to carry a rifle loose like that in the cabin of his truck, the farmer said. He reached into his pocket for some more bullets, which he tucked into the .22’s brass cartridge case with work-thickened fingers. The snake still twitched a bit. Bernard hoicked it over the wire fence into the heath beyond the dirt road.

A few minutes after this I asked Steve if he’d like to take another look at it. In truth I didn’t want to go alone because, against my rational good sense, I feared that the snake would come back to life, like Rasputin from under the ice. We climbed through the fence and searched among the gravel and low bushes. Before long we found our snake, very dead, lying in a misshapen ‘S’ on a patch of broken limestone in the sun. You could see where the bullets had kinked its spine and pushed small blooms of flesh through its hide. Steve lifted it up by the head and showed me its long retracted fangs. Some big red sergeant ants arrived and began keenly investigating the wounds. Within a minute dozens of others were approaching.

We turned around and headed back to camp where Lewis was stooped over a breadboard filleting up the morning’s catch of fish, and Bernard frying it up in a cloud of fragrant smoke. They were silent and concentrated, finding comfort in the mundane precision of these regular tasks. The stubbies they had opened on the snake’s death sat warming on the dirt beside them.

Our campfire was kept going almost constantly with she-oak wood and mallee roots, and kilos of fish were fried at all times of day and night. Even though it was summer; most nights were cold and windy. One evening as we all sat around a glowing root, Jenny said that it was a pity no one had a guitar. Jan spluttered that ‘thank Christ there wasn’t’ – a guitar had ruined many a good campfire.

On our last afternoon, I took a big sheet of glue-primed paper down to the beach and attempted a larger oil of the dune-grasses, with a thin line of sea beyond. Because I paint flat on the ground, I’d been having problems with oil paint, sand and the wind. This time I laid as many rags as I could on the beach around me and created a barrier out of a towel and my backpack to windward. I bashed away at this for a few hours until it ended up with a texture not unlike a non-slip decking, yet not as bad as before.

That evening was January 31st, and we celebrated New Year’s Eve a day early, at nine o’clock instead of midnight, drinking a little more than usual and eating some more fried fish. Bernard shook the fillets in a plastic bag of flour and salt and threw them into a wok of hot oil.

That night I dreamt that I’d cut off each of my legs at the top of the thigh with a sharp fishing knife. Filled with remorse, I managed to join them up again, but they made a crunching sound when I walked. This sound became louder and louder until I awoke up and realised it was coming from just outside our tent. I banged my feet against the canvas and hissed, but it didn’t go away. By torchlight Jan and I saw a bandicoot digging a hole in the dirt right up against the tent entrance. It looked up at us with a bored expression and kept digging.

In the morning I asked Bernard if he thought eating a lot of fish gave you strange dreams. He said it was probably the cheap red wine I drank.

We packed our borrowed station wagon, carefully sliding all Jan’s parents’ camping gear into its neatly sewn bags. I laid my wet sand-dune painting on top. Then we drove through the hot day almost all the way to Perth until we reached a settlement called Crosslands and a farm driveway advertising ‘Apricots For Sale’. A handsome woman with grey hair pulled into a ponytail showed us through to a large pergola, long-established and leaning south. I bought four cobs of corn and kilos of apricots for Jan’s father to make jam with. There was an enormous fig tree outside - the biggest I’d ever seen - and I remarked to the woman that the birds must love it. She said they did, but that the figs left uneaten at the bottom more than sufficed their needs. ‘We share it very well with the birds’, she said, smiling.

That evening we ate the corn at the kitchen table of Jan’s parents’ house in the northern suburbs of Perth. We all agreed that it was good and sweet, and I regretted buying so few cobs.

The night was hot and windless, and towards dawn I was woken by the reticulation sprinklers popping out of the lawn next to our window. In the semi-darkness, squeezed between Jan and the sleeping boys, with the hissing water outside, and imagined Lewis and Steve (who had stayed on) getting ready for the day’s fishing. Taking some fresh mulies from the Esky and rolling them in old copies of the West Australian, pulling tight the salt-rusted buckles of their faded backpacks and wading off through the deep sand of the track.